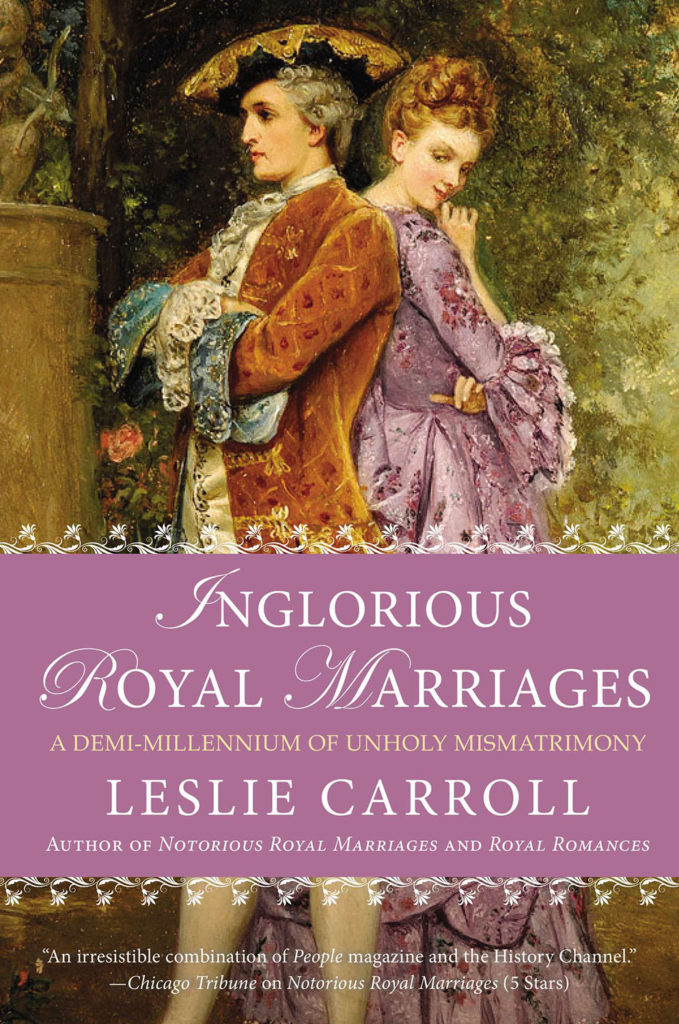

Inglorious Royal Marriages

Buy the Book:

Buy the Book: Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Books-A-Million

IndieBound

Published by: NAL Trade

Release Date: September 2, 2014

Pages: 400

ISBN13: 978-0451416766

Overview

Why does it seem that the marriages of so many monarchs are often made in hell? And yet we can’t stop reading about them! To satisfy your schadenfreude, INGLORIOUS ROYAL MARRIAGES offers a panoply of the most spectacular mismatches in five hundred years of royal history….some of which are mentioned below.

When her monkish husband, England’s Lancastrian Henry VI, became completely catatonic, the unpopular French-born Margaret of Anjou led his army against the troops of their enemy, the Duke of York.

Margaret Tudor, her niece Mary I, and Catherine of Braganza were desperately in love with chronically unfaithful husbands—but at least they weren’t murdered by them, as were two of the Medici princesses.

King Charles II’s beautiful, high-spirited sister “Minette” wed Louis XIV’s younger brother, who wore more makeup and perfume than she did.

Compelled by her mother to wed her boring, jug-eared cousin Ferdinand, Marie of Roumania—a granddaughter of Queen Victoria—emerged as a heroine of World War I by using her prodigious personal charm to regain massive amounts of land during the peace talks at Versailles. Marie’s younger sister Victoria Melita wed two of her first-cousins: both marriages ultimately scandalized the courts of Europe.

Brimming with outrageous real-life stories of royal marriages gone wrong, this is an entertaining, unforgettable book of dubious matches doomed from the start.

Backstory

Why is it that we can never seem to get enough gossip about celebrities and their relationships (especially when they go belly-up)? We seem obsessed with reality TV shows, supermarket tabloids, and the blind items that dot Page Six of the New York Post. For some reason, love gone wrong seems even more exciting—and juicier—than stories of happily-ever-after.

My fourth nonfiction volume about royal lives, ROYAL ROMANCES, offered readers a number of real-life love stories, from happy marriages to tales of royal mistresses who were the sovereign’s true Grand Passion.

So, with the fifth book in the “royal” series, I decided that it was time to spin the wheel 180 degrees and choose to shine the spotlight on some of the numerous disastrous royal unions throughout the ages. INGLORIOUS ROYAL MARRIAGES: A Demi-millennium of Unholy Mismatrimony spans five hundred years of mismatches, opening with the marriage of England’s Henry VI and Margaret of Anjou during the era known as the Cousins’ War (later called, and better known as the Wars of the Roses) and closing with the marriages of two sisters, granddaughters of Queen Victoria, who were related to all of the principal players in what was initially nicknamed The War of Cousins (later called and better known as The Great War, The War to End All Wars—neither of which it was, sadly—and World War I).

As with all of the “royal” books, there was an embarrassment of riches when it came to selecting whom to include. The royals in INGLORIOUS ROYAL MARRIAGES are inter-generationally linked, like a dysfunctional daisy chain. Although readers may cherry-pick their favorites and enjoy the chapters out of order, reading the book straight through provides a historical continuum, reminding us that while the more things may change in terms of warfare, fashion, and technology, when it comes to marriage, the more they stay the same.

Excerpt

“And love is a thing that can never go wrong;/And I am Marie of Roumania,” the American humorist Dorothy Parker satirically quipped in the Roaring Twenties, when the glamorous sovereign, one of Queen Victoria’s multitudinous grandchildren, was the most famous royal on the planet. The instant recognition of Marie’s name, and her reputation as the victim of an unhappy, arranged marriage, have become lost to subsequent generations; but her rocky nuptial road mirrors that of countless royal spouses.

Because these royal unions were intended to be political and dynastic strategic alliances, nearly all of them were arranged, even through the Victorian era. No one expected the spouses to be in love, or even to love each other; and yet their families and friends would always act surprised when the man and wife barely got along, and the marriage failed. A much-anticipated “glorious” life of glamour, wealth, and power was doomed or destroyed, not only by such connubial disasters as adultery or infertility, but by the banalities of real life and the natural emotional reactions to marital neglect. The only reason so many of these unions lasted was because divorce was invariably unthinkable, or legally unattainable. The rare royal divorces brought scandal and disgrace on the entire dynasty. As Czar Nicholas II opined—at the end of the nineteenth century—when two of his first cousins horrified the family by calling it a day, the death of a dear loved one would have been preferable to a divorce. One wonders if Nicholas might have felt differently had he been trapped in a miserable union, instead of having the good fortune of wedding his one true love.

Every royal marriage in this volume makes the hit parade of history’s myriad mismatches. And as much as it’s true that some marriages were more terrible than others, it’s hardly surprising that there were so many bad ones; several of the girls were only in their mid-teens when their parents sacrificed them on the altar of matrimony to grooms who were total strangers, barely older than their brides.

The idea that mere adolescents were routinely expected to make the weighty decisions required of governing a kingdom, to lead armies, make policy decisions, and set the nation’s tone in fashion and culture, is mind boggling today. Their brains had not yet fully matured; how could they have the requisite judgment to wisely rule? By the time these children—and that’s what they were—had wed at the age of fifteen or sixteen, they had reached their legal, if not emotional, adulthood, and no longer had a regent to do the heavy lifting. Yes, they had ministers, and in some situations there was a parliament; but the monarch had a tremendous amount of authority and in many cases, the last word.

When you add to the burden of king- or queenship that of parenthood at such a young age, as well as the fact that there was usually no rapport between the spouses, it’s no wonder so many of these marriages were miserable. But what if there were no children—a different problem altogether? Royal wives had one major duty, even if they were the rulers: to bear an heir for the kingdom. When trouble in the bedroom, for any number of reasons, resulted in childlessness for an extended number of years, or even for the duration of the marriage, it was the wife who was blamed. She could be sent back to her native land in humiliated disgrace or shoved into a convent and forced to become an abbess—the inglorious marriage annulled so that her husband could try again with a more potentially fertile womb. The world would know that she had failed her spouse, her family, and her country.

And when she crossed the invisible boundaries prescribed for her sex by evincing an interest in affairs of state or any area perceived to be a man’s sphere, including having the temerity to question her husband’s extramarital infidelities, she was cast as hysterical, a harridan, or an unnatural woman. Society was rarely kind to females, but in many ways, royal women enjoyed an even narrower world with fewer choices than commoners. They could not seek employment or professionally practice a craft. They might become patrons of artists, industries, or charities, but could never be an entrepreneur. It was imperative for a royal wife to be charming and gracious, but if she was outspoken or had strong opinions, she was viewed as a meddler. She was supposed to be elegant, but if she was too glamorous or flamboyant, she was derided for behaving like a royal mistress.

Yet many of the queens and other first ladies of their respective realms managed to overcome their marital disappointments in a variety of ways, from taking the reins of power to indulging in adulterous affairs. The aforementioned Marie of Roumania, who was compelled by her mother to wed her jug-eared, shy, unassertive, and boring cousin Ferdinand, became the “face” of her little-known country during the First World War, regaining massive swaths of land during the peace talks at Versailles through her personal charm and what I have dubbed “couture diplomacy”—simply knowing the right thing to wear!

Others became warrior queens like Margaret of Anjou; yoked to the childlike Henry VI of England, whose sudden paralytic illness rendered him incapable of ruling his realm, she raised an army during the Wars of the Roses, hell-bent on saving her husband’s throne.

Some royals were united with men who batted for the other team: For Marie of Roumania’s younger sister Victoria Melita, known as “Ducky,” things didn’t go so swimmingly in the marriage bed. Her first husband, also a first cousin, the Grand Duke of Hesse, preferred footmen and stable boys—which was less of a scandal than Ducky’s subsequent divorce and elopement with another first cousin, a Russian Grand Duke! The hypocrisy is astounding. Until very recently, divorced persons were personae non grata at the English court and were not even permitted into the Royal Box at Ascot, although for centuries, known adulterers swanned about with impunity within the royal inner circle.

During the seventeenth century, Charles II’s beautiful, high spirited sister “Minette” wed the younger brother of Louis XIV, her French cousin Philippe d’Orléans, a man who wore more makeup and perfume than she did. Although the duc d’Orléans was able to fulfill his marital duty with Minette, when she died young he didn’t find it as easy to propagate with his second wife, a butch-looking, zaftig German princess. One night, she caught him hanging holy medals about his genitalia, which he insisted enabled him to rise to the necessary level of performance. Philippe’s father, Anne of Austria’s husband, Louis XIII of France, wasn’t particularly interested in women either. It took nearly a quarter-century before Anne bore an heir. Although there were a number of miscarriages, absent a live birth she was blamed for the problems in the boudoir and stigmatized for her barrenness.

In some marriages, the love was hopelessly one-sided. Both England’s Mary I (Henry VIII’s older daughter, known as “Bloody Mary”) and the diminutive Portuguese-born princess Catherine of Braganza, were tragically in love with their husbands. But their respective spouses, Philip II of Spain and Charles II, never returned their affection. Nicknamed the “Merry Monarch” for the jubilant and libidinous era inaugurated by his Restoration of the monarchy, Charles went so far as to flaunt his numerous mistresses in front of his lovestruck wife for the duration of their twenty-three-year marriage! And Henry VIII’s older sister Margaret Tudor was the dupe of not one, but three husbands who were incapable of fidelity.

At least these women survived to complain about their mistreatment—unlike Lady Jane Grey, wed against her will, and a victim of her parents and in-laws’ ambition. Ditto, the two gorgeous Medici princesses Isabella Romola de Medici and Eleonora di Garzia di Toledo, who learned the hard way that in Renaissance Italy powerful husbands could behave with impunity; their wives—not so much.

Italian men created their own rules, as Marie Antoinette’s older sister Maria Carolina learned when she wed Ferdinand IV, King of Naples. His wife and subjects had no choice but to laugh and applaud when their sovereign dumped hot pasta on their heads at the opera house and made passes at every signorina in sight. Married to a buffoon, Maria Carolina became the decision maker at a crucial point in Neapolitan history, with Napoleon encroaching from all sides.

An overarching behavioral pattern emerges in many of the unions profiled here. Perhaps it was the fact that these royal couples couldn’t easily extricate themselves from a bad marriage. Consequently, a parabola of matrimonial misery can be drawn, beginning with mutual indifference on the part of the spouses, who in most cases scarcely knew each other, but certainly hadn’t viewed their mate with anything approaching passionate attachment, As the marriage progressed, familiarity did indeed breed contempt, if not utter loathing—often fertile ground for adultery. However, by the end of some of the more lengthy marriages, the sparring spouses had become as comfortable together as a pair of bedroom slippers, settling into a benign state of tolerance and acceptance, occasionally sharing a platonic friendship that was solidified by their mutual devotion to their children. By the time death took one of them from the other, the survivor was often surprised by the intensity of their grief: it was a poignant realization, but a little too late to do anything about it.

The remarkable real-life stories in Inglorious Royal Marriages are interconnected; among the heroes and heroines of these connubial catastrophes are some of Europe’s most famous monarchs, as well as others whose lives may be less familiar to readers. Providing context and key events of their reigns, including Readeption, Reformation, restorations, and revolutions, this compendium of royal love gone wrong proves that once again, real life is often stranger—and juicier—than fiction!