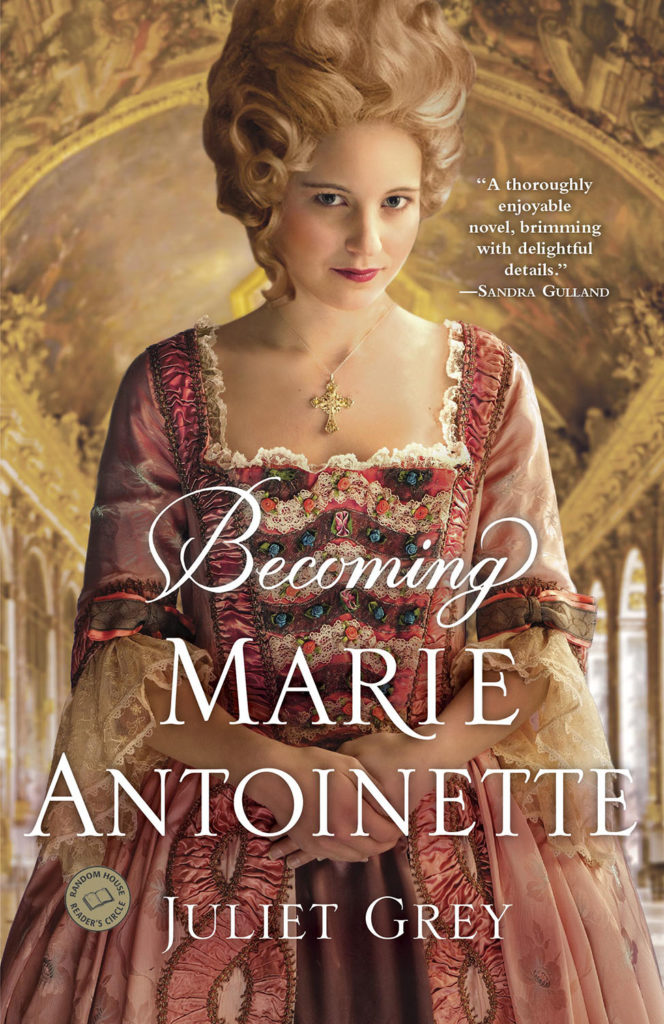

Becoming Marie Antoinette

Buy the Book:

Buy the Book: Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Books-A-Million

Published by: Ballantine Books

Release Date: August 9, 2011

Pages: 480

ISBN13: 978-0345523860

Overview

Much has been written about Marie Antoinette, whose ascent to power-and steep downfall during the French Revolution-is legendary. But BECOMING MARIE ANTOINETTE offers a fresh perspective on Marie Antoinette’s young life, a topic mostly overlooked by historians until now. In this elegant and entertaining novel, Juliet Grey looks beyond the crown to the sacrifices a young, spoiled girl was compelled to make long before she could become the queen of France who would leave an indelible mark on history.

Marie Antoinette’s young life was a long series of hurdles. She sailed over a few of them with grace and equanimity. But some she stumbled over. Among vivid scenes in the Austrian imperial court in Vienna and the gilded splendor and manicured gardens of Versailles, we learn that Maria Antonia’s relationships with everyone from her cold ambitious mother to her awkward teenage husband, were fraught with a dramatic tension all their own.

In 1766, ten-year-old Austrian archduchess Maria Antonia learns that she is to one day wed the heir to the throne of France, its dauphin Louis Auguste. But she is far from ready to embrace her glittering destiny. Raised alongside her numerous siblings by the powerful and politically ambitious Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, Maria Antonia undergoes a startling makeover before leaving her homeland at the age of fourteen to marry the awkward teenage boy who will one day become king of France. This grueling transformation includes sharp and painful orthodontia, four-hour hairstyling sessions, and lessons in perfecting the “Versailles Glide,” the elegant mode of traversing the magnificent halls of the French château. These historically accurate details bring this remarkable, often rocky and emotionally arduous coming-of-age story to fresh and vivid life. Out of her element and out of her depth, the teenage dauphine, naïve, homesick and unloved, must learn to navigate her way through the French court, a labyrinth of glamour and treachery, never sure whom to trust. The novel ends on May 10, 1774, the day that Louis XV, the grandfather of Marie Antoinette’s husband breathes his last. A bright and glorious future await Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette, now king and queen of France.

Praise

“A thoroughly enjoyable novel, brimming with delightful details. Grey writes eloquently and with charming humor, bringing ‘Toinette’ vividly to life as she is schooled and groomed-molded, quite literally-for a future as Queen of France, an innocent pawn in a deadly political game.”

-Sandra Gulland, bestselling author of Mistress of the Sun and The Josephine Bonaparte Trilogy

“A lively and sensitive portrait of a young princess in a hostile court, and one of the most sympathetic portrayals of the doomed queen.”

-Lauren Willig, bestselling author of The Pink Carnation series

“Wonderfully delectable and lusciously rich, an elegant novel to truly savor. Juliet Grey’s Marie Antoinette is completely absorbing.”

-Diane Haeger, author of The Queen’s Rival

“[A] sympathetic take on the fascinating and doomed Marie Antoinette.”

-Publishers Weekly

“An extremely compelling read. The author blends very intricately detailed research with a narrative that is stunning in its poignancy.”

-The Elliott Review

“Full of sumptuous and well- researched details . . . Becoming Marie Antoinette by Juliet Grey, the first novel in a new trilogy, gives readers a more sympathetic look than usual at the ill- fated French queen.”

–Philadelphia Examiner, five stars

“In her richly imagined novel, Juliet Grey meticulously recreates the sumptuous court of France’s most tragic queen. Beautifully written, with attention paid to even the smallest detail, Becoming Marie Antoinette will leave readers wanting more!”

-Michelle Moran, bestselling author of Madame Tussaud

“This is historical fiction at its finest.”

– A Library of My Own

“Fans of historical fiction will eat this one up. It’s engaging, smart, and authentic. Grey has done her homework.”

– January Magazine

“Grey possesses the rare ability to transform readers to a past only accessible by imagination. Becoming Marie Antoinette is sure to appeal to lovers of quality historical fiction.”

-The Well Read Wife

“[A] lively, well- written promenade through pre- Revolution France . . .

It’s history with a spoonful of sugar- and that’s never a bad thing.”

-The Decatur Daily

“C’est magnifique! A very entertaining read, one that I was hard pressed to put down and am waiting (ever so impatiently) for book two in the trilogy.”

– Passages to the Past

“Smart, yet extremely engaging . . . Becoming Marie Antoinette will please fans of historical fiction.”

– Confessions of a Book Addict

“A great read that is sure to be requested by lovers of historical fiction, especially those who enjoyed Michelle Moran’s Madame Tussaud and other novels about the French Revolution.”

-Library Journal

“Everything is so vividly described that you feel as though you are right there experiencing it all. This novel is very well written and it captivates you from the very beginning.”

– Peeking Between the Pages

“It is a captivating and well thought out book, and one that raises this woman of history to the point of a living person, which the reader finds easy to identify with, and relate to.”

– The Book Worm’s Library

Backstory

I fell in love with Marie Antoinette (and Louis) while I was researching their marriage for NOTORIOUS ROYAL MARRIAGES one of my works of nonfiction, written under the name Leslie Carroll. The more I read about them, the more it became apparent that they have truly been misrepresented and misinterpreted by historians. They say history is written by the winners, and Marie Antoinette and Louis were the two greatest victims of the French Revolution.

What sparked BECOMING MARIE ANTOINETTE specifically is how little has been told about her childhood years and the incredible makeover she had to endure at the hands of a small army of experts before she was judged acceptable marriage material, while the clock was ticking and a vitally strategic international alliance hung in the balance. The preadolescent Marie Antoinette was worked over by a hairdresser who reconfigured her hairline so that her forehead would not appear too prominent; a dentist who realigned her teeth with orthodontia, a pair of actors who became dialect coaches for her pronunciation of French; a notable dancing master who taught her the “Versailles Glide,” the walk that was unique to the women of the Bourbon court; and a gentle cleric who came to tutor her in academics. My novel also shows just how much the young Austrian archduchess Maria Antonia was a political pawn, moved about the European chessboard by her mother, the formidable Hapsburg empress Maria Theresa, and King Louis XV of France.

Excerpt

ONE

Is This the End of Childhood?

Schönbrunn: May 1766

My mother liked to boast that her numerous daughters were “sacrifices to politics.” I never dared admit to Maman, who was Empress of the Holy Roman Empire, that the phrase terrified me more than she could know. Every time she said it, my imagination painted a violent tableau of Abraham and Isaac.

Unflinchingly pragmatic, Maman prepared us to accept our destinies not only with grace and equanimity, but with a minimal amount of fuss. Thus, I had been schooled to expect, as sure as summer follows spring, that one day my carefree life as the youngest archduchess of Austria would forever change. What I never anticipated was that the day in question would come so soon.

In the company of my beloved sister, Charlotte, I was enjoying an idyllic afternoon on the verdant hillside above the palace of Schönbrunn, indulging in one of our favorite pastimes-avoiding our lessons by distracting our governess, the Countess von Brandeiss.

A bumblebee hummed lazily about our heads, mistaking our pomaded and powdered hair for dulcet blossoms. Charlotte had kicked off her blue brocaded slippers and was wiggling her stockinged feet in the freshly cut grass. So I did the same, delighting in the coolness of the lawn, slightly damp against the soles of my feet, although we’d surely merit a scolding for staining our white hose. Affecting a grim expression and pressing my chin to my chest until I achieved our mother’s jowly appearance, in a dreadfully stern voice I said, “At your age, Charlott-ah, you should know better than to lead the little one into childish games.”

My sister laughed. “Mein Gott, you sound just like her!”

Countess von Brandeiss suppressed a smile, hiding her little yellow teeth. “And you should know better than to mock your mother, Madame Antonia.

“Ouf!” Startled by the bee, which now appeared to be inspecting with some curiosity the ruffles of her bonnet, our governess began to bat the air about her head. Nearly tripping over her voluminous skirts as she leapt to her feet in fright, Madame von Brandeiss began to hop about in such a comical fashion that it was impossible for us to feel even the slightest bit chastised.

Maman’s scoldings were so easy to duplicate because they came with far more regularity than her compliments. From middle spring through the warm, waning days of September, she was a familiar presence in our lives, tending to affairs of state from the outskirts of Vienna in our summer palace of Schönbrunn, a grand edifice of ocher and white that resembled a giant tea loaf piped with Schlag, whipped cream. With scrubbed faces we were presented to her in the Breakfast Room, its walls, the color of fresh milk, partitioned into symmetrical panels by gilded moldings and scrollwork. Charlotte, Ferdinand, Maxl, and I looked forward to the invitation to the day when we would be old enough to merit an invitation to join her, along with our older siblings, for a steaming pot of fragrant coffee and terribly adult conversation about places like Poland and Silesia, places I remained unable to locate on the map of Europe that hung on the wall of our schoolroom.

For the remainder of the year, when the prodigious Hapsburg family resided at the gray and labyrinthine Hofburg palace in the heart of Vienna, we, the youngest of the empress’s brood, scarcely saw Maman more than once every ten days. We even attended daily Mass without her, a line of ducklings, dressed in our finest clothes, kneeling on velvet cushions that bore our initials embroidered in silver thread. Charlotte and I remained side by side as our pastel-colored skirts, widened by the basketlike panniers beneath them, nudged one another; our heads swam with the pungent aroma of incense while our ears rang with ritual-the resonance of the grand pipe organ and the bishop’s solemn intonations in Latin.

And as the days grew shorter we began to forget the woman who had almost dared to have fun during those departed sunlit months. Mother became matriarch: a forbidding figure clad all in black, her skirts making her appear nearly as wide as she was tall. Marched into her study for inspection, we would stand still as statues-no fidgeting allowed-while she peered at us through a gilt-edged magnifying glass and inquired of our governess whether we were learning our lessons, eating healthy meals, using tooth powder, and scrubbing our necks and behind our ears. The royal physician, Dr. Wansvietten, was put through the same paces with questions about our general health. The answers were invariably in the affirmative, since no one would dare to admit any act of negligence or weakness, and so she dismissed us from her presence, satisfied that we were dutiful children.

I slid across the grass on my bottom, nestling beside our governess, adjusting my body so that I could whisper in her ear, “May I tell you a secret, Madame?”

“Of course, Liebchen.” Madame von Brandeiss smiled indulgently.

“Sometimes . . . sometimes I wish you were my mother.” The pomade in her hair, scented to disguise its origin as animal fat, smelled of lavender. I closed my eyes and inhaled deeply. The fragrance was so pleasant, it nearly made me sleepy.

“Why, Madame Antonia!” The countess managed to appear both touched and alarmed, her cheeks coloring prettily as her gray eyes stole a reflexive glance to see who might be listening. “How can you say such a thing, little one-especially when your maman is the empress of Austria!”

Madame von Brandeiss tenderly stroked my hair. I could not remember whether my mother had ever done so, nor could I summon the memory of any similar display of warmth or affection. It was enough to convince me that they had never taken place. I felt my governess’s lips press against the top of my head. Somehow she knew, without my breathing a word, that the empress’s demeanor rather frightened me. “I’m sure your maman loves you, little one,” she murmured. “But you must remember, it is the duty of a sovereign to attend to great and serious affairs of state, while it is a governess’s responsibility to look after the children.”

I wriggled a bit. My leg had become entangled in my underskirts and had fallen asleep. “Are you ever sorry you didn’t have any of your own?” I asked the countess. Inside my white stockings I wiggled my toes until the tingling was gone.

“Antonia, you’re being impertinent!” Charlotte said reproachfully. “What did Maman tell you about blurting out whatever comes into your head?” I loved and admired my next oldest sister more than anyone in the world, but she had the makings of quite a little autocrat-Maman in miniature in many ways. Already her adolescent features had begun to resemble our mother, especially about the mouth.

Ignoring my sister, I tilted my chin and gazed earnestly into our governess’s eyes. “If you could have, would you have had sixteen children, like Maman?” There were only thirteen of us now, owing to the ravages of smallpox. I’d contracted the disease when I was only two years old and by the grace of God recovered fully. Only a tiny scar by the side of my nose remained as a reminder of what I had survived. When I grew older I would be permitted to hide it with powder and paint, or perhaps even a patch, although Maman thought that women who covered their pox scars withmouches had no morals. “If you had a little girl, Madame, what would you want her to be like?”

Countess von Brandeiss swallowed hard and fingered the engraved locket about her neck. She was perhaps nearly as old as Maman; the brown hair that peeked out from beneath her straw bonnet and white linen cap was threaded with a few strands of silver. She tenderly kissed the top of my head. “If I had had a little girl, I would have wanted her to be just like you. With strawberry blond curls and enormous dark blue eyes, and a generous heart as big as the Austrian Empire.” Tugging me toward her, she readjusted the gray woolen band that smoothed my unruly tendrils off my forehead. It wasn’t terribly pretty but it served its turn, and was ordinarily masked by my hair ribbon. But that afternoon I had removed the length of rose-colored silk and used it to tie a bouquet I plucked from the parterres-tulips and pinks and puffy white snapdragons.

“Yes, Liebchen,” sighed my governess, “she would be exactly like you, except in one respect.” I looked at her inquiringly. “If I had had a little girl, she would be more attentive to her lessons!” Madame von Brandeiss gently clasped my wrists and disengaged my arms from her neck. Her eyes twinkled. “She would not be clever enough to invent so many distractions, and she would pay more attention to her studies. And, she would not ask so many”-she glanced at Charlotte, who was feigning interest in splitting a blade of grass with her pale, slender fingers- “impertinent questions.

“Now,” she said, urging me off her lap and onto the lawn. “Enough games. Like it or not, ma petite, it is time for your French grammar lesson. You too, Charlotte.” The countess clapped her hands with brisk efficiency. “Allons, mes enfants.”

In the blink of an eye, a liveried footman handed Charlotte our copybooks.

Before I could stop myself, I pursed my lips into a petulant little moue. Our governess stuck out her lower lip, playfully mocking my expression. “You mustn’t pout, Antonia. It was you, little madame, who convinced me to move your lessons out of doors today.”

Rolling onto my belly and propping myself on my elbows, I lifted my face to the breeze and filled my nostrils with the scents of summer. The boning in my bodice pressed against my midriff and my skirts belled out above my rump like a pink soufflé. “But I’m not pouting, Madame. It’s how God made me,” I said brightly. In truth, what Maman calls “the Hapsburg lower lip” gives the impression of a permanent pout, even when I’m not sulking. Our entire family looks the same way; with fair hair, a pale complexion, and a distinctly receding chin, I resembled every one of my siblings and ancestors.

And yet, if I’d had a glass I would have appraised my appearance. Was I pretty? Maman thought I was a perfect porcelain doll, but I’d overheard whispers among the servants. . . something about the way I carried my head. Or perhaps it was my physiognomy. Then again, I was a Hapsburg archduchess. I had every reason to delight in my lineage. Still-I wanted everyone to love me. If there were a way to please them, I wished to learn it. “Do you think my chin makes me look haughty?” I asked Madame von Brandeiss.

“People who have nothing better to do will indulge in idle gossip,” our governess replied. Charlotte placed her hand over her mouth to hide a smile. “Your chin makes you look proud. And you have every reason to be proud because you are a daughter of Austria and your family has a long and illustrious history. And,” Madame von Brandeiss continued, beginning to laugh, “you are doing it again.”

“Doing what?” I asked innocently.

“Doing everything you can think of to avoid your books. Don’t think you can fool me, little madame.”

She clapped her hands again. “Come now, you minxes, you’ve dawdled enough. Vite, vite! It’s time for your French lesson.” She shook Charlotte gently by the shoulder.

Charlotte rolled onto her back and sat up; she was diligent by nature, but if I began to dally, she could become as indolent as I when it came to our schoolwork. Our moods affected each other as if we had been born twins. Her grumble became a delighted squeal as something caught our eyes at exactly the same moment. “Toinette, look! A butterfly!” My sister shut her copybook with a resonant snap. Joining hands, we pulled each other to our feet and began to give chase. Without breaking her stride Charlotte swept up her net from where it lay in the soft grass with a single graceful motion.

“Ach! Nein! Girls, your shoes!” Madame von Brandeiss exclaimed, rising and smoothing her skirts. Her boned corset prevented her from bending with ease; she knelt as if to curtsy and scooped up one of my backless ivory satin slippers.

“No time!” I shouted, clutching fistfuls of watered silk as I hitched up my skirts and raced past Charlotte. The butterfly became a blur of vivid blue as it flitted in an irregular serpentine across the manicured hillside, its delicate form silhouetted against the cerulean sky. It finally settled on a hedge at the perimeter of the slope. Charlotte and I had nearly run out of wind; our chests heaved with exertion, straining against the stiff boning of our stomachers. My sister began to lower her net. I raised my hand to stay her. “No,” I insisted, panting. “You’ll scare her off.”

I held my breath. Gingerly reaching toward the foliage, I cupped my hands over our exquisite quarry. The butterfly’s iridescent wings fluttered energetically, tickling my palms. “Let’s show Madame,” I whispered.

With Charlotte a pace or two behind me, limping a bit because she’d put her foot wrong on an unseen twig, I cautiously tiptoed back across the lawn, fearful of tripping and losing the delicate treasure cocooned within my hands. The rapid trembling of the butterfly’s wings gradually slowed until there was only an occasional beat against my palms.

Finally, we reached the countess. “Look what I’ve got!” I crowed, slowly uncurling my fingers. The three of us peered at the motionless insect. Charlotte’s face turned grave.

Catching the troubled expression in her pale blue eyes, “Maybe she’s sleeping,” I said softly, hopefully, stroking one of the fragile wings with my index finger. My hands were smudged with yellow dust.

“She’s not sleeping, Toinette. She’s . . .” Charlotte’s words trailed off as she looked at me, her usually flushed cheeks now ashen with awareness.

My lips quivered, but the sobs became strangled in my throat. Drawing me to her, Charlotte endeavored to still the heaving in my shoulders, but I shrugged her off. I didn’t deserve to be comforted. An enormous tear rolled down my cheek and landed on my chest, marring the silk with an irregular stain. Another warm tear plopped onto my wrist. I closed my hands again as if to shelter the butterfly in the sepulcher made by my palms, while the full weight of my crime settled on my narrow shoulders.

“I. Didn’t. Mean. To. Kill. Her. I’ve. Never. Killed. Anything. I would. Never. Hurt . . .” My sobs finally came in big loud gulps, bursts of hysterical sound punctuated by apologies.

With a look of sheer helplessness I threw myself into my governess’s open arms.

“Shh, Liebchen,” soothed the countess, caressing my hair. “We know you meant no harm.” For several moments I remained in her embrace, my cheek pressed against the ruching at her bosom. Then Madame von Brandeiss knelt before me and used her lace-edged handkerchief to blot my tears. “Perhaps,” she said, gently taking my clasped hands in hers, “perhaps she was too beautiful to live.”