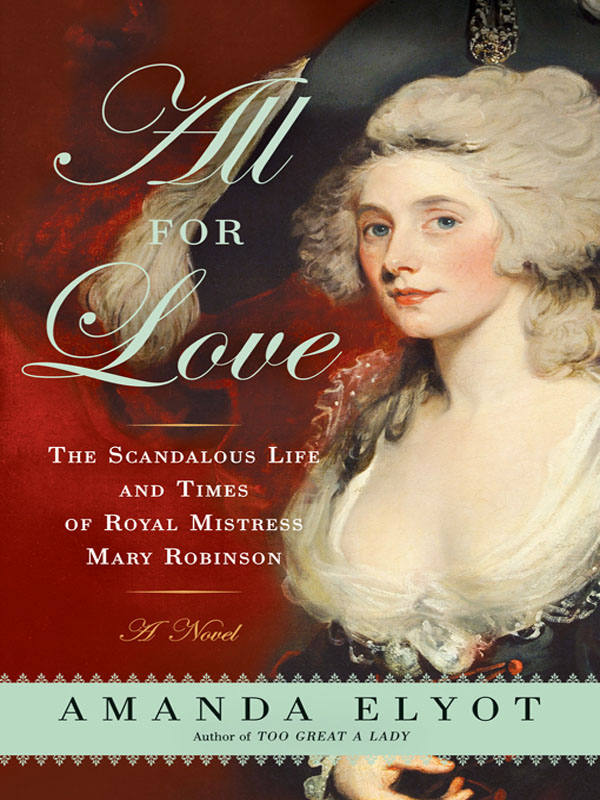

All for Love

Buy the Book:

Buy the Book: Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Published by: NAL Trade

Release Date: February 15, 2008

Pages: 448

ISBN13: 9780451222978

Overview

Overnight she became a star. Over many nights she became a legend.

At the age of fifteen, Mary Robinson was married off to an unfaithful wastrel. During the next seven years, her spellbinding talent, beauty, and drive would lead her from the denigration of debtors’ prison to the London stages, where a star was born. With the heart of a poet and face of an angel she was sold as society’s darling. Though dubbed “the priestess of taste” for her dashing style, her unabashed exploits made her the queen of scandal, envied by women worldwide, and desired by every man within reach.

From Mary Robinson’s shocking affair with the Prince of Wales and the fortuitous liaisons that titillated the country, to heartbreaking betrayals and a restless pursuit of true romance, this breathtaking novel paints a vivid portrait of a woman who changed history by doing as she pleased-for money, for fame, for pleasure, and above all—for love.

Praise

Historical romance queen Elyot shines her light on Mary Darby Robinson (1758-1800), who, during her brief life, burned with a passionate intensity. Mary’s daring and anguished existence is truly the stuff of novels-her own writings, particularly her feminist essays, were acclaimed in her lifetime-and Elyot’s telling of her life, in Mary’s voice, honors her legacy.

~Publishers Weekly

Heartfelt and believable.

~Sarah Johnson, Historical Novels Review</strong>

Impeccable research and beautifully written . . . an amazing peek into the life of a remarkable woman.

~Romance Reviews Today

Backstory

I discovered Mary Robinson in 2006 when I read a review of Paula Byrne’s biography-one of three biographies of Mary Robinson to be published in Great Britain within a two-year window.

I was floored. Mary Robinson (1757-1800) was the most famous person I’d never heard of! Her life reads like a who’s-who of eighteenth-century arts and letters. As a fledgling poetess, the collection of verses that enabled her family to break free of debtors prison, was sponsored by Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire. She was mentored by David Garrick and Richard Brinsley Sheridan, becoming the brightest luminary of the London stage when she was still in her teens. She had love affairs with the Prince of Wales, the Whig firebrand Charles James Fox, and the American Revolutionary War hero known as the “scourge of the Carolinas,” rising Liverpool politician Banastre Tarleton. As a writer and editor, and—toward the end of life—an outspoken feminist, her path crossed those of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Godwin, and Mary Wollstonecraft.

Although Mary Darby Robinson was born into the burgeoning middle class, her life, like Emma Hamilton’s, was crammed with so many exciting events and so many connections to the era’s best-known personalities that her story begged to be immortalized in historical fiction. I was also drawn to Mary because she was a professional actress who became a bestselling novelist. I got the greatest kick out of incorporating Mary’s actual complaints about the publishing business, which she put into the mouths of some of her literary heroines in my own novel about her life. I’m still not sure whether I was delighted or dismayed to discover that some things never change.

Readers Guide

1. When she was only seven years old, Mary Darby’s father abandoned his family. How much of her life do you think was shaped by this event?

2. Mary’s parents, particularly her father, were very much against her ambitions for a theatrical career. Do you agree with their decision? How much of what Mary experienced do you think was due to the fact that she became a celebrated actress, and how much was due to other factors? If you think the latter plays a part, what other factors do you think shaped her destiny?

3. Mary’s mother was keen to see her enter a respectable marriage, regardless of Mary’s own desires, marrying her off when she was in her mid-teens, young even for the Georgian era. Given the period in which these women lived, and the maturity level of a relatively sheltered fifteen-year-old girl, was Mrs. Darby right? Was Mary right? What would you have done if you had walked in either of their shoes?

4. In order to become the prince’s mistress, Mary gave up a lucrative career and a financial independence that was very rare for a woman of her day. Do you think she was justified in insisting on an annuity after he ended the relationship?

5. Mary lived at a time and in a society where a member of the gentry and lower classes could not get a divorce. Clearly she endured countless humiliations from her wayward husband, but was bound to him for life. Do you blame her or applaud her for seeking-and finding-love and happiness in the arms of other men? What would you have done if you were in the same situation?

6. Smart women, foolish choices. Or not. Why do you think Mary remained with Tarleton for the better part of fifteen years? What did each of them get from the relationship? Have you ever been there yourself?

7. In a letter written to William Godwin toward the end of her life, Mary referred to Maria as “my secondself.” Maria stuck by her mother for all the days of her life. What do you think of this decision? Why do you think Maria never married? Contrast that to why Jane Austen never married.

8. In the last year of her life, Mary was jailed for debt. By law, a husband was financially responsible for his wife, including paying her debts, whether they resided together or not; yet Mary, who was ill and in pain at the time, chose imprisonment, rather than involving Mr. Robinson (whom she hadn’t seen in years) in her predicament. What do you think of this decision, given Mary’s complicated relationship with her husband and debts?

9. Mary is considered one of the first “celebrities.” She was the subject of extensive gossip among all strata of society. Her every action was noted and written about in the papers, and she had no compunction about getting good press by “puffing” herself. Women wanted to emulate Mary’s fashion sense, yet at the same time she was considered vulgar-not just because of her many (and much-publicized) love affairs, but because self-promotion of any kind was thought to be unfeminine and immodest. If Mary lived today, with whom do you think she’d be sharing the tabloid headlines? What differences might she find between her own society and ours? What similarities might she find?

10. Mary was considered a literary pioneer for using her own life experiences in her writing. As a poetess she experimented with scansion and meter, and Coleridge and Wordsworth openly acknowledged her influence on their own work. In her novels, Mary’s uncanny skill in holding a mirror up to the foibles of contemporary society presages the sly wit of Austen and Thackeray, two authors whose names and novels live on and remain widely read. Mary Robinson was immensely prolific, writing in more genres (poetry, novels, comedies, tragedies, satires, operas, philosophical essays, and journalism) than any other female writer of her time-and yet relatively little of her vast body of work is available today. It isn’t regularly studied in high schools and universities. Discuss why this might be the case. Now that you know about her life, are you interested in reading Mary’s novels and poetry?

11. In Mary’s 1799 novel The Natural Daughter, the publisher Mr. Index counsels the heroine, a budding author, on how to write a surefire bestseller: fictionalize a real-life scandal, give it a provocative title, and the readers will devour it. Has much has changed since then?

12. Had you heard of Mary Robinson before you read this novel? Now that you know something about her, what do you think her legacy is?

Excerpt

Chapter 1

More Sensibility than Sense

One night in 1765 . . . my eighth year

“Dream well, my rosebud,” my handsome father whispered. As Papa bent down to kiss me good night, his olive-tinted skin smelled comfortingly of bay rum and tobacco. I cherished the low rumble of his voice; when it was the very last sound I heard at bedtime, I knew the next day would be a lucky one. In the half-light, for then I feared to fall asleep in total darkness, I could still make out his striped waistcoat with its shiny brass buttons.Even as he tucked me into bed he looked like he was preparing to head off to the exchange.

But in the middle of that night I was shaken awake by the sound of raised voices. My parents rarely quarreled, so deep was the affection that ran between them. Mother saw Papa as I did: strong, kind, and generous.

“Their schooling, Nicholas.What do you expect me to do? Surely you do not expect proper English children to grow up like savages in the wilderness? Mary is the darling of the Miss Mores. And when Miss Hannah took her girls to see Mr. Powell in King Lear at the Theatre Royal, Mary was in raptures for weeks, eager herself to tread the boards. Miss Hannah even wrote a special part for her in one of her dramatic parables.”

“I merely thought, my dear, since you can scarcely bear to spend a moment apart from any of the children, that it would be more amenable to you to take them with us. If their education concerns you more than their companionship, perhaps it would be better to leave them here.”

“And board them somewhere? With strangers? I don’t even board Mary at the Miss Mores.”

“I am endeavoring to please you, Hester. It is only because of my esteem for you that I leave this decision in your hands, rather than ordering you to do your duty as my wife in whichever manner I see fit.”

“And I thank you for that, my love. But each prospect seems so terrible to me. It is not just the health of their minds that I fear. Illness, dampness, droughts, disease-before we even reach Greenland’s shores-not halfway to our destination-we shall be compelled to endure weeks of being tossed to and fro in the middle of the sea like so many crates of tea, with no one to hear our cries should we become imperiled. My stomach turns at the merest thought of our accommodations.”

My father grew testy. “Hester, I expect to be abroad for two years, perhaps longer. I should not ask you to join me on this venture, were I not keenly aware of its dangers and equally certain of your safety and of the children’s. You must think me a monster to believe that I would ever willingly put my family at such risk.”

“How can it not be a risk?”

“Are you refusing to accompany me?”

The saddest and most plaintive moan escaped my mother’s anguished lips. “Nicholas . . . I dared not breathe a word of this to you, certain you would find it silly . . . I have such a horror of the ocean that it mortifies me to confess it. And I fear that even for your own dear sake, such dread is not to be borne, much less overcome.”

Her words might as well have been made of iron, forming the nails for her coffin. Mother spoke her mind, revealing her darkest fears to the man she loved with every fiber of her being, and was to pay a horrible price for it.

In my early years growing up in Bristol, though I had three brothers, I was still my father’s favorite. I was the one who’d replaced their little Elizabeth-the pink angel they lost to the pox before she reached the age of three. We were cosseted, petted, and spoil’d as rotten as week-old cabbage, given the finest of everything as befitted the children of a successful-though often absent-British merchant and his doting wife.

I never was permitted to board at school, nor to pass a night of separation from the fondest of mothers. Mother adored her handsome husband and he delighted in her sweet and open nature. I recall caresses, even kisses, exchanged in front of my brothers and me, and gifts were bestowed in abundance. Mother’s jewels were enviable, for my father possessed exquisite taste and the money to put it to good use.

I slept on crimson damask sheets in a bed fit for a princess. My dresses were ordered from London. We dined on the very best china and plate. And during the summer months we were sent to Clifton Hill for the advantages of a purer air. Mother was the kindest of women; if she had any faults, it was her too tender care that she lavish’d upon my brothers and me.

My father was a North American born of black Irish stock, a man of strong mind, high spirit, and personal intrepidity, and it was all three of those noble qualities that removed him from his family on more than one occasion. But from the moment of that midnight quarrel, my life’s course took its first shattering turn, for Papa had devised an eccentric scheme as wild and romantic as it was perilous to hazard-and it would take him away from us forever.

In my romantic girlish mind my thoughts of him would fluctuate as if riding astride a pendulum. In one instant he was the American Seafarer, off on another exotic venture to a faraway and savage land; but in the next moment Papa was the British Merchant who would desert the family he adored when, surely, closer to hand there were equally prosperous projects to be explored. Caught between worshipping him and being cross with him for leaving all of us to fend as we might in his absence, I was as quick to defend him as I was to condemn. He broke my heart as often as he mended it.

After many dreams of success and many conflicts betwixt prudence and ambition, when I was but seven years old, Papa departed for Labrador to establish a whale fishery amongst the Esquimaux Indians there, believing he could civilize them and teach them the necessary skills that would eventually make British America’s whaling industry topple that of Greenland, its greatest rival. It turned out to be a double farewell, for my elder brother, John, was sent off to Italy at the same time, apprenticed to a mercantile house in Leghorn.

My parents corresponded as frequently as practicable. At first, their letters were full of fondness, even ardor, for each other, as well as Mother’s fears for Papa’s health and safety, and his repeated tender assurances that all was well and that he missed his adoring family dreadfully. He would return to England even wealthier; as triumphant for himself as for the economy of king and country; and every day would be a holiday under the Darby roof. But gradually, the tone of his letters began to change. Warm affection was supplanted by a civil cordiality, as if he now wrote from duty, rather than desire. My mother felt the change, and her affliction was infinite.

“Why did I not conquer my fears?” she lamented to me, as she pressed my auburn curls to her bosom. “Why did I let my own timidity divide me from the very man to whom I pledged myself, body and soul, and consigned my fortunes?”

At length, a total silence of several months awoke my mother’s mind to the sorrows of neglect, the torture of compunction. “Has he forsaken us for my trepidation?” she would worry aloud.

And then, one horrible day, the penny dropped.