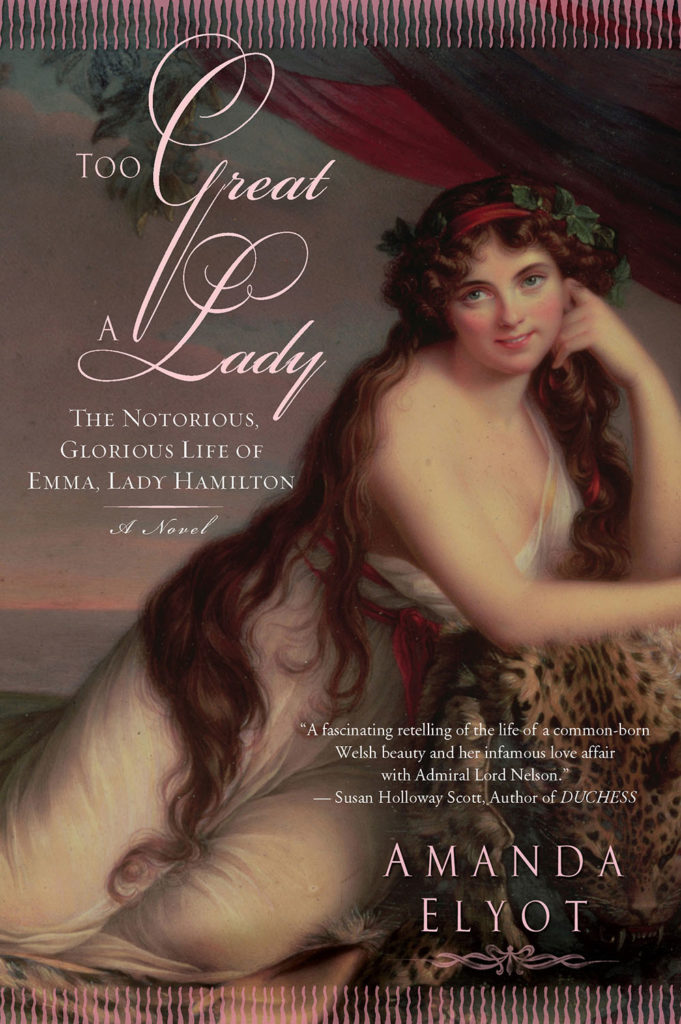

Too Great A Lady

Buy the Book:

Buy the Book: Amazon

Barnes & Noble

Published by: NAL Trade

Release Date: February 6, 2007

Pages: 432

ISBN13: 9780451220547

Overview

Emma Hamilton is renowned as the real-life heroine of the greatest love story in British history: yet her passionate and enduring romance with Lord Horatio Nelson remains the stuff of legend.

She had the accent—and mouth—of a bawdy Welsh maid, but Emma’s breathtaking beauty captivated some of the most influential and powerful men in Europe The impoverished daughter of an illiterate country farrier, young Emily Lyon sold coal by the roadside to help put food on the family’s table. By the time she was fifteen, she had made her way from London nursemaid to vivacious courtesan, and continued a meteoric rise through society, rung by slippery rung. And by the end of the eighteenth century, she had become the most talked-about woman in all of Europe, an artful performer, an ambassador without portfolio, mistress of many tongues, a key envoy in Britain’s and Italy’s war against the French, and confidante to a queen. Once she met Nelson, Emma’s fascinating life grew even more tumultuous, as she and England’s greatest hero of the age braved the censure of king and peers, and the sneers of society, all in the name of true love.

This novel, inspired by her remarkable life, recounts Emma’s many extraordinary adventures, the earth-shattering passion she eventually found with Lord Nelson, and how they braved the censure of king and country, risking all in the name of true love.

Praise

Elyot gives Emma a rippingly bawdy, occasionally self-aggrandizing first-person, that . . . rings true. The result is an energetic portrait of a unique historical figure.

~Publishers Weekly

Backstory

I can’t remember when I first “met” Emma Hamilton because it feels like there’s never been a time when I haven’t known her. I used to kid people about being her reincarnation because the empathy I felt for her was so visceral. I would visit her portrait in the Frick Museum when I was in high school, just to say hello.

I sold the novel to Crown on a sentence. “I’d like to tell Emma Hamilton’s story from her POV,” I told my editor, right after I turned in the manuscript to By a Lady—in those days when editors actually read hard copies—and rang for the Random House elevator. Rachel’s reply was “Great! I love her!!” So I went home, read about forty books on the story’s principals and the late Georgian and early Regency eras, and the book poured out of me. I traveled to England for the bicentenary celebration of Nelson’s death at Trafalgar and toured the Admiralty with its historian and the HMS Victory in the company of experts on Nelson’s navy.

Then my editor moved on and her successor had barely heard of Emma Hamilton, let alone loved her with the passion and fire that we did. Although fully written, the novel was now homeless. But Too Great a Lady soon sold to NAL and remains one of my favorite books, even though that’s a bit like choosing a favorite child. I grew so fond of Sir William Hamilton that I cried when it was time to write his death scene. And after reading several biographies of Nelson, although he was undoubtedly a hero, I discovered that he wasn’t such a saint. His flaws made him all the more human and interesting to me as a man. I collected Nelsoniana and Emma memorabilia, which sat on my desk as I researched and wrote the novel. I have a bust of Nelson made from copper taken from the Foudroyant, Nelson’s flagship during the time he and Emma consummated their romance. She may even have become pregnant with their daughter Horatia during their lovemaking on board the vessel. And I have two signatures of Emma’s, probably snipped from tradesmen’s IOUs. The anonymous nineteenth-century note that came with them refers to Emma as the “widow of the late Lord Nelson of Trafalgar.”

I got a lump in my throat when I read it. She would have been so pleased.

Readers Guide

1. The passionate love affair between Emma and Nelson was real life that became romantic legend. Although divorces were extremely difficult to obtain during that era, both Emma and Nelson were committing adultery. How do you feel about that? Given the hypocritical moral standard of the day (“It’s okay as long as you’re discreet”), and the state of their respective marriages at the time Emma and Nelson began sleeping together, do you accept, or condone, their romance?

2. Given your discussion on the previous question, when soul mates find each other, should true love conquer all?

3. The three principal characters in the novel-Emma, Nelson, and William Hamilton-are drawn from actual people, and their fictional actions are derived from actual events. Each is undeniably flawed, as real human beings undoubtedly are. Do their flaws help you better understand their actions? Do these flaws (discuss them) make you sympathize with them—or not?

4. Emma and her mother have a rather atypical relationship, and yet an utterly symbiotic one. What do you make of it? Do you think Mam should have tried to be more present during Emma’s difficult teenage years, or do you think she did all she could under the circumstances (hers and Emma’s)?

5. Bearing in mind the era in which this novel is set, do you agree that the life of a courtesan or kept woman is preferable to an “honest” life as a servant, factory worker, or farm laborer? Do you think the former profession gives a woman more independence and autonomy than any or all of the latter trades mentioned? If you lived in the mid-to-late eighteenth century, which life would you choose, if faced with a similar dilemma to Emma’s?

6. Do you think the British Crown and the Admiralty were right to come between Nelson and Emma and make life difficult for each of them, as a sort of “punishment” for their public displays of affection? Do you think Nelson’s love for Emma had any impact on his nobility? Or on his ability to serve his king and country just as bravely and effectively as he did before he met Emma? Do you think the government should have stayed out of Nelson’s personal life? Do you think they were right in ignoring his dying wishes and the terms of his codicil?

7. Do you believe that a leader’s personal life-regardless of whether you agree with or condone his behavior—should have any bearing on whether he should retain his position or remain a leader, as long as he continues to be effective? Can you think of more contemporary events than Nelson and Emma that spark a parallel?

8. Do you think societal hypocrisy and appetite for scandal is any different now than it was 200 years ago?

9. Emma paid a terrible price for a past that she endeavored to overcome, proving herself a model of fidelity, particularly during the years from 1786 (when she traveled to Naples) to late 1799 (when she and Nelson commenced their affair). Yet royalty, and high society, scorned and shunned her, or refused to admit her into their homes (while still enjoying her Attitudes and her hospitality at Palazzo Sessa), citing not only Emma’s former “dissolute” life but her low birth, which rendered her ineligible to mingle in their midst. How do you feel about the way Emma was treated?

10. If you lived in Emma’s day, what strata of society might you have fit, or been born, into? How do you think others might have treated you?

11. Would you have shunned, or welcomed, Emma? Would she have been a friend?

12. Emma is a flawed heroine, as many of us might be, should our lives become the stuff of fiction. Which of Emma’s many attributes do you find less than admirable? Which qualities do you admire?

Excerpt

Prologue

26 April 1814

12 Temple Place

Within the Rules

My sin has found me out.

But it was a sin born of devotion to the greatest man England has ever produced, to protect the glorious name of Horatio Nelson from the taint of his detractors.

I owe the world a confession. It is true that last month I publicly denied the authenticity of a two-volume compendium purporting to be the love letters written betwixt myself and Lord Nelson. At the time, my vehement refutation proceeded from the earnest desire to honor the dead, who cannot speak for themselves, as well as to respect the reputations of the living. I have a child to look after. who must command my devotions—Horatia Nelson—the only offspring of England’s greatest hero since St. George and a mother, who, as I once told a shopkeeper, was too great a lady to be mentioned.

In truth, I am the woman. I am the heroine of the greatest real-life love story in England’s long and tempestuous history. Robin and Marian, gamboling on the greensward in Nottingham, are perhaps more famous than Nelson and Emma, but they are quaint creatures of folklore, when all is said and done. The passions of Arthur, Guinevere, and Lancelot delight our senses, but they are merely glorious inventions of the writers’ pens. My passions are not fancies on the silver tongues of medieval minstrels. My passions live and breathe at this very moment, in the shadow of a guttering candle resting on a rickety table within a squalid flat in the confines of a debtors’ prison. I am the woman who began her life as the daughter of an illiterate farrier and his wife, only to rise, rung by slippery rung, through the ranks of society to become the most talked-about woman in Europe. I am she for whom the gallant Nelson risked all in the name of true love, bravely hazarding the censure of his monarch and his peers. When he sailed forth into battle to defend his king and country from their greatest enemies, it was my portrait that he wore about his neck as a talisman from his guardian angel, and he died with my name upon his lips.

As I write these words on the evening of my forty-ninth birthday, from my two windows overlooking Temple Place I can glimpse the grand illuminations outside the Surrey Theatre, and, in front of the marquee, the Surrey’s acrobats performing their circus tricks for the cheering crowds. All day, the bells of London have rung as any man will tell you they have not done in living memory. But the fanfare is not for me, though I have done many services for my country. They are celebrating Napoleon’s enforced abdication, thanks to England’s new champion—Arthur Wellesley. “Rule Britannia” is being sung boisterously in every tavern. Cries of “It’s all up with Boney!” echo through the fetid, narrow streets of the Rules. But as a condition of my imprisonment I am not permitted to attend a theatre or partake of the jubilation; a visit to a tavern or to a place of entertainment is deemed by the authorities to be “escaping.”

Yet perhaps it is just as well, for on this still-chilly night my heart cannot soar with those of John Bull. I despair to think that only a few short years since Trafalgar, the name of Wellington has already dimmed the star of Nelson in the memory of the common man. But it shall not eclipse his name-no! Not while I live to fan Nelson’s flame and remain the stalwart and protective keeper of his living legacy to his country.

If the particulars of my extraordinary life, including the confessions of my intimacy with the illustrious Lord Nelson, are to be disclosed with verisimilitude, they must perforce proceed from my own pen, and not from the greedy presses of scurrilous scandalmongers. I was the one who lived it, and my story is not a prize to be boarded and taken at will. Before heaven I vow to defend the truth, mine honor, and my heart with such unceasing broadsides that it will make the very devils of hell deaf from my cannons’ thunder. I am writing for my life, and that of my thirteen-year-old daughter, that I might earn enough from the sale of this memoir to break the debtors’ shackles and raise Nelson’s only child in a manner befitting her birthright. Whether to exalt or to excoriate, I intend to spare no one my candor.

Begging your indulgence, I hope you will be entertained, if nothing greater, by my extraordinary adventures on this earth, and I wish you every felicity.

Emma Hamilton

~

Chapter One

The earliest days

“Oh, Emy, it’s just a bit of fun is all!”

“Let go, Peter! I mean it, let me go!” Though he tried to hold me down, I kicked as hard as I could, and my long bare leg made contact with his belly. “Quit it, John Buckley!” Like a feral cat, I clawed at pimply Peter Flint with one hand whilst with my other I clutched at my calico, trying to keep my skirts down.

The boys pushed me onto my back in the mud by the edge of the road, heedless of my tears and shouts. I was nigh on twelve years old and they was fifteen or sixteen, taller than I was; and I knew they wouldn’t have thought twice about using their swagger sticks to beat me had I continued to refuse them. “Just give us a squeeze and a fondle,” John insisted. “Show us your pretty, round bubbies.” John grabbed hold of my bare feet and began to drag me into a ditch where we mightn’t be spotted from the road and where for certain my virtue would become just a memory.

“We just want to see what else it is you’re selling!” Peter reached into my apron pocket and grabbed a few lumps of coal. I peddled the coal by the roadside, helping my gammer, Sarah Kidd, put bread and bacon on the table for the seven of us who dwelt crammed together like coop hens in her little cruck cottage, “the Steps.” Laughing, as if to mock me, Peter lobbed the precious cargo across the road.

“I’m not on offer!” But the two country boys, loutish and poorly shod despite Hawarden’s windy damp, had taken the notion to misunderstand me.

Through the years, the same life lesson has appeared in my copybooks and recollections. In the world of men, it appears to be a maxim that a beautiful and charming woman is—regardless of her station or fortune—available. In their view, it all depends on her price. A truly extraordinary beauty, such as I was—for all the greatest painters of the day said so, and my portraits hung in every fashionable salon—was simply more costly to afford.

The ugly childhood memory returns. Just as I thought I was done for, along come Gammer up the Chester Road on her way back from the market in her rattletrap of an empty wagon, a picturesque peasant woman in her striped woolen garments, her graying hair hidden by a kerchief and a soft-brimmed hat. I heard the whish of her whip before I saw its long leather tongue catch fat John right between the shoulder blades, landing with a crack like the snap of a dry twig.

“Get!” she yelled, scaring the shite out of them. They backed away from me like jackrabbits, fumbling with their plackets. Leaving me lying in the ditch, they tried to scramble up to the road, but Gammer’s whip caught ’em both across the cheeks with a single blow. “There’s summat to remember the afternoon by,” she added. “And if I catch you near my Emy again, I’ll bost your heads afore you can come up with your next thought.” Then, for good measure, she took the whip to their hides again while they tried to outrun its reach. “Did they ‘arm you, girl?” she demanded when she saw I was covered with scratches.

“No, but they was trying. You come just in time, Gammer. These cuts come mostly from fighting ’em off, though maybe John managed to brush one of my bubbies when he was reaching to tear my frock away. It’s too small for me anyhow, y’nau,” I said, looking down at the straining fabric. “Would’a bost itself soon enough.”

“I should ‘ave noticed it myself, child,” Gammer said, clucking her tongue against her teeth. “I expect I just didn’t want to see what was plain as the nose on my face. You outgrew that bodice months ago and your skirts is barely reaching your ankles, but I was ‘oping we might get ’em to last a mite longer.” She climbed down from the wagon, undid her kerchief, and dried my tears before folding me in her arms.

“You’re getting far too old to stand in the Chester Road anymore. You’re becoming a beauty, Emy, and I’ll not ‘ave your charms exposed to everyone as passes. It’s time for me to find you a proper situation.”

“No!” My eyes filled with tears. “I love it ‘ere! You can’t make me go!” I said, growing angrier by the moment. Truth was, I hated Hawarden and dreamed of a grander life filled with color and warmth, exactly the opposite of our chilly, damp, gray corner of North Wales. My father, Henry Lyon, died when I was but two months in this world, and Mary, my mam, had gone down to London in the hopes of better employment when I was but a tot. But Gammer was my world. I loved her more than anyone and could not begin to imagine being without her.

Gammer tenderly stroked my head until my sobs subsided into whimpers. Then, after scrutinizing my disheveled condition, she concluded, “A lick and a promise’ll do for washing these cuts clean, y’nau? Now ‘op up beside me, girl, so we can get on ‘ome afore the deeleet fades.”

After supper she tucked me into bed as if I were still her little Emy. My grandfather and Uncle William dozed over the table, Grandpa snoring enough to shake the rafters loose. My aunts knit stockings by the guttering flames of our tallow candles, and, muttering almost silently to themselves as they counted their stitches, took no notice of anything else.

Gammer sat beside me and struck up a pretty, rustic air. I joined her on the second verse, inventing a light harmony. When she turned her face to mine at the end of the song, there were tiny teardrops in the corners of her eyes. “You’ve truly the voice of one of the angels, my girl,” she said softly. Her words sounded like music, despite-or perhaps because of-her countrified speech.

“I don’t want to be leaving you, Gammer,” I sniffled. “I don’t want to take a position anywhere else.”

“Husht thee naise,” she said gently, smoothing a curl off my forehead. “Hawarden’s no good place for you anymore. The world’s a big wide thing, child, and you best be moving into it, so’s you can begin to make your way on your own. You might even learn to curb that fierce temper of yours, which could only be to the good.” Gammer leaned down and kissed the top of my head. She smelt of the turnips she’d boiled and mashed for our supper and I was missing her even before I was gone. “Now, shut those deep blue eyes of yours, Emy, and we’ll talk more about it in the deeleet.”