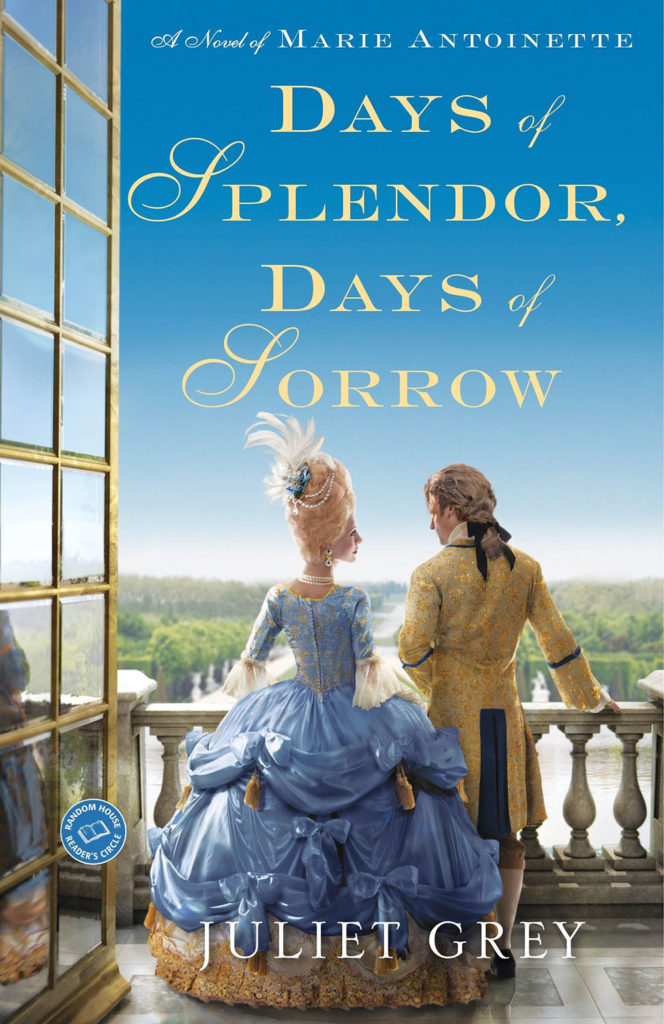

Days of Splendor, Days of Sorrow

Buy the Book:

Buy the Book: Amazon

Apple Books

Barnes & Noble

Books-A-Million

IndieBound

Published by: Ballantine Books

Release Date: May 15, 2012

Pages: 448

ISBN13: 978-0345523884

Overview

A captivating novel of rich spectacle and royal scandal, Days of Splendor, Days of Sorrow spans fifteen years in the fateful reign of Marie Antoinette, France’s most legendary and notorious queen.

Paris, 1774. At the tender age of eighteen, Marie Antoinette ascends to the French throne alongside her husband, Louis XVI. But behind the extravagance of the young queen’s elaborate silk gowns and dizzyingly high coiffures, she harbors deeper fears for her future and that of the Bourbon dynasty.

From the early growing pains of marriage to the joy of conceiving a child, from her passion for Swedish military attaché Axel von Fersen to the devastating Affair of the Diamond Necklace, Marie Antoinette tries to rise above the gossip and rivalries that encircle her. But as revolution blossoms in America, a much larger threat looms beyond the gilded gates of Versailles-one that could sweep away the French monarchy forever.

Praise

“Grey succeeds in illuminating the humanity of this much maligned, misunderstood, and tragic queen.”

—AmoXcalli

“For those wishing an indepth interpretation of Marie Antoinette’s life, this trilogy is perfect. Exceptionally well done!”

—Historical Novel Review

“It’s obvious that Grey has done her research on Marie Antoinette’s life and world. . . .once again Grey excels at descriptions of fashion and location . . . the book provides readers with an interesting look into Marie Antoinette as she goes from beloved young queen to hectic gambler to a more mature and yet detested figure in the eyes of the French people.”

—Vivelaqueen

“The attention to history and detail is perfect in this novel. . . .Grey really does offer the best portrayal of Marie Antoinette in historical fiction.”

—Examiner.com

“This book was very well researched and one of the things I enjoyed most about this one and the first in the series is how real Grey makes Marie and Louis seem and how well she captures the grandeur of the French court.”

—Bippity Boppity Book

“Juliet Grey creates an unforgettable tapestry of court intrigue, royal scandals, and dangerous romances, all set against the spectacular background of Versailles. [A] sympathetic tale [and] a marvelous sequel, setting the stage well for Grey’s final installment of this mesmerizing trilogy.”

—BookLoons Reviews

“Juliet Grey’s second installment in her trilogy about Marie Antoinette retains the same incredible writing, detailed descriptions, and illustrious character development as the first installment contained. . . .Despite knowing the grisly end that most of the characters face it is impossible to not be drawn into their lives and hope for a different fate. Please, Ms. Grey, write the third and final installment quickly!”

—Romance Junkies, 5 blue ribbons

“You can feel the tension, love and sorrow as if you were there.”

—The History Nerd

“Juliet Grey is an absolute master at bringing 1700s Versailles alive.”

—Book Drunkard

“Every little detail in this book is delectable. . . . Written in good taste, nothing is amiss, and everything is possible.”

—Enchanted by Josephine

Backstory

It provided great pleasure, but also left me with a measure of sadness, to continue the story of Marie Antoinette’s life in Days of Splendor, Days of Sorrow, because of course we know the tragic denouement. I felt that part of my role in this middle novel in the trilogy was to show how Marie Antoinette’s journey continued along its fatal path. It’s clear from the book’s epigraph, taken from a quote at the time she ascended to the throne as the queen consort of Louis XVI, that she was considered a liability. Add that to all the animosity that had built up against her, particularly within the French court, during the four years she was dauphine-an effervescent teenage girl making enemies right and left as she pushed with all her might against the rigid etiquette of Versailles.

One can go back even further to the 950 years of enmity that existed between France and Marie Antoinette’s native Austria, a political albatross hung around her pale and slender neck almost as soon as her betrothal to the future Louis XVI was arranged. When her mother, the Hapsburg Empress Maria Theresa, sent her to France in April 1770, she exhorted her youngest daughter to make the French love her. With a few notable exceptions, that admiration came mostly during the late reign of Louis XV, who by then was roundly despised by his subjects. The charming (and morally upright) strawberry-blond dauphine and her husband were seen as the great young hopes for France’s future.

But Marie Antoinette’s popularity soon faded as the propaganda spread that she was not comporting herself with the dignity of a French queen and was, moreover, behaving like a royal mistress by decking herself out in increasingly elaborate jewels, gowns, and other accoutrements such as the outrageous (and outrageously expensive) towering “pouf” coiffures. Her subjects, convinced by propaganda disseminated from within Versailles itself, published by nobles she had angered by ostracizing them from her intimate circle, soon saw her as the queen of excess.

Marie Antoinette’s behavior predates the study and practice of psychoanalysis, but inDays of Splendor, Days of Sorrow I aimed to convey the genesis of her extravagance and what lay behind her increasing mania for pleasure. It was of course primarily a substitute for what she most desired-a child, especially a son and heir-not only for the security of the Bourbon dynasty, but because she adored children. Her life might have taken a different trajectory had she conceived early in her marriage. Instead, her first child, a daughter, was born in the waning days of 1778, a frustrating and embarrassing eight and a half years after her nuptials-ample time for her enemies to recast the religiously devout and faithfully wed young queen as a promiscuous hedonist.

What happened on her wedding night was immortalized by Louis in his hunting journal with a single word: rien. Nothing-although the reference was really a notation that the bridegroom had not killed any woodland creatures that day because he’d not gone hunting. Not only was Louis shy and uncomfortable around his new bride, but he may have suffered from a mild deformity of the penis known as phimosis, where the foreskin is too tight to retract. This condition made intercourse, and even an erection, painful.

Historians’ opinions are divided as to whether Louis suffered from phimosis and underwent a minor procedure (not as radical as circumcision) in late 1773 to correct the defect (for narrative reasons I placed the event in 1774 after he became king); or whether his inability to make love to Marie Antoinette was purely psychological or psychosomatic. The latter is harder to believe because Louis admitted that he both loved and respected Marie Antoinette and found her very beautiful. While a number of present-day scholars vehemently dispute the phimosis speculation as being the pet theory of Marie Antoinette’s twentieth-century biographer, the Freudian Stefan Zweig, they cannot explain away the preponderance of correspondence that came out of the Bourbon court at the time. This included not merely the dispatch from the Spanish ambassador to his sovereign graphically discussing the issue of Louis’s penis (which could be dismissed as gossip), but a number of letters written between Marie Antoinette and her mother discussing whether or not Louis was prepared to submit to the operation, and the medical opinions of the various court physicians on the subject. The language of that correspondence most clearly refers to a physical problem. Whether it was compounded by psychological and emotional issues is also a possibility. Unfortunately, Louis’s boyhood tutor, the duc de la Vauguyon, had instilled in him a hatred of women and a particular distrust of Austrian females. But by 1773, the dauphin and dauphine had become close friends, and presented a united front against the duc’s malevolent influence. This was even truer by the time they ascended the throne in 1774.

The subject of Louis’s phimosis and how it was treated is one a couple of controversial topics I explore in this novel. I do believe that he suffered from a mild physical deformity and that he underwent a corrective procedure, although it was nothing as major as a circumcision. The operation detailed in the novel is taken from a procedure performed in France around 1780 so it is about as accurate a description as one can get of what Louis’s medical treatment might have been like.

Another of my aims in writing the Marie Antoinette trilogy was to convey the humanity (and sometimes not) within these historical figures. Too often they have been depicted in film and literature as archetypes, stereotypes, or dusty relics of an era long past. As I breathed life into characters who to some readers may be little more than names from a history book, I saw them as vibrant and vital, complex and flawed. It was also my intention to depict some of the less well-known (but equally fact-based) events of the characters’ lives. For example, the silk merchants of Lyon really did pay a call on Mesdames asking for their support after Marie Antoinette began to dress almost entirely in the muslin gaulles; Marie Antoinette really did suffer a terrible fall and hit her head and Madame Royale’s shocking reaction to her mother’s injury as well as the conversation she had with her father about whether he would have preferred a son instead of her, really happened. I was stunned when I first read about the incident in the many biographies because it revealed so much about the characters, both of the precocious and envious Madame Royale, and the king, who was a tremendously sentimental man. Louis indeed adored his little girl from the moment of her birth and never resented her gender, despite all the immense pressure upon both him and Marie Antoinette to produce a son and heir. The fact that both of them were such sentimental, vulnerable, and fairly hands-on parents, made them quite anomalous, especially for royals, even in the Age of Enlightenment. In another fascinating moment “ripped from real life,”the queen did indeed summon Jean-Louis Fargeon to le Petit Trianon to create a perfume that captured the essence of her private idyll (I own a replica of the fresh, floral scent, which made my research all the more redolent!). And she did ask Fargeon to develop a unique fragrance for a man she described as “virile as one can possibly be,” that phrase, in translation of course, taken from the perfumer’s own diary. In a subsequent event, to be depicted in the third book of the Marie Antoinette trilogy, many years later the aroma of that custom-made toilet water will come back to haunt Fargeon’s nostrils.

One of the central aspects of this novel is the developing relationship between Count Axel von Fersen and Marie Antoinette. Historically, there has been some controversy as to how far it went, whether it remained strictly platonic, whether (and when) it may have blossomed into a physical love affair, and whether Marie Antoinette ever violated her deeply held marriage vows and consummated her passion for Fersen.

I have a cardinal rule about writing historical fiction: If it could have happened, bolstered by solid research, then it’s fair game to be included in a novel. Stanley Loomis in The Fatal Friendship: Marie Antoinette, Count Fersen, and the Flight to Varennes, offers enough compelling evidence for a relationship between them that may indeed have eventually been consummated. Biographers Antonia Fraser, Stefan Zweig, Vincent Cronin, and André Castelot share that opinion. We have the culture of the eighteenth century to thank for the plethora of diaries and memoirs left to posterity. Some may be more reliable than others, depending on the source. After Marie Antoinette’s death, Fersen’s beloved sister Sophie, to whom he was especially close, burned a number of his letters; and at some point (perhaps after his gruesome murder on June 20, 1810, which took place exactly nineteen years to the day from the royal family’s fateful flight to Varennes in June of 1791, an event that will be dramatized in the third novel of the Marie Antoinette trilogy), his diaries were heavily redacted.

However, enough of Fersen’s own words remain that obliquely hint at a relationship with Marie Antoinette that went far deeper than the proper bounds of a common friendship. We have his declaration to Sophie that he would never wed because he could not be united with the one woman he really loved and who loved him in return. As historians cannot document any abiding yet for some reason inappropriate or equally illicit relationship that he had with another woman (his other love affairs, regardless of their duration, were fairly inconsequential by comparison), the conclusion is viable (certainly by a novelist), that he gave his heart and soul (and the case can be made for giving his body) to Marie Antoinette.

Excerpt

~ONE~

Queen of France

May 8, 1774

To: Comte de Mercy-Argenteau,

Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to the Court of Versailles:

My Dear Mercy,

I understand that the death of my sovereign brother is imminent. The news fills me with both sorrow and trepidation. For as much as I account Antoinette’s marriage to the dauphin of France among the triumphs of my reign, I cannot deny a sense of foreboding at my daughter’s fate, which cannot fail to be either wholly splendid or extremely unfortunate. There is nothing to calm my apprehensions; she is so young, and has never had any powers of diligence, nor ever will have-unless with great difficulty. I fancy her good days are past.

~Maria Theresa

***

~La Muette, May 21, 1774~

“My condolences on the passing of His Majesty, Your Majesty.”

“Your Majesty, my condolences on the death of His Majesty.”

“Permit me, Votre Majesté, to tender my deepest condolences on the expiration of His Majesty, Louis Quinze.”

One by one they filed past, the elderly ladies of the court in their mandated mourning garb, like a murder of broad black crows in panniered gowns, their painted faces greeting each of us in turn-my husband, the new king Louis XVI, and me. We had been the sovereigns of France for two weeks, but under such circumstances elation cannot come without sorrow.

Louis truly grieved for the old king, his late grand-père. As for the others, the straitlaced prudes-collets-montés, as I dubbed them-who so tediously offered their respects that afternoon in the black-and-white tiled hall at the hunting lodge of La Muette, I found their sympathy-as well as their expressions of felicitations on our accession to the throne-as false as the blush on their cheeks. They had not loved their former sovereign for many decades, if at all. Moreover, they had little confidence in my husband’s ability to rule, and even less respect for him.

“Permettez-moi de vous offrir mes condoléances. J’en suis desolée.“ I giggled behind my fan to my devoted friend and attendant Marie Thérèse Louise de Savoie-Carignan, the princesse de Lamballe, mimicking the warble of the interminable parade of ancient crones-centenarians, I called them. “Honestly, when one has passed thirty, I cannot understand how one dares appear at court.” Being eighteen, that twelve-year difference might as well have been an eternity.

I found these old women ridiculous, but there was another cause for my laughter-one that I lacked the courage to admit to anyone, even to my husband. In sober truth, not until today when we received the customary condolences of the nobility had the reality of Papa Roi’s death settled upon my breast. The magnitude of what lay before us, Louis and me, was daunting. I was overcome with nerves, and raillery was my release.

The duchesse d’Archambault approached. Sixty years of rouge had settled into her hollowed cheekbones, and I could not help myself; I bit my lip, but a smile matured into a grin, and before I knew it a chuckle had burbled its way out of my mouth. When she descended into her reverence I was certain I heard her knees creak and felt sure she would not be able to rise without assistance.

“Allow me, Your Majesty, to condole you on the death of the king-that-was.” The duchesse lapsed into a reverie. “Il etait si noble, si gentil . . .“

“Vous l’avez detesté!” I muttered, then whispered to the princesse de Lamballe, “I know for a fact she despised the king because he refused her idiot son a military promotion.” When the duchesse was just out of earshot, I trilled, “So noble, so kind.”

“Your Majesty, it does not become you to mock your elders, especially when they are your inferiors.”

I did not need to peer over my fan to know the voice: the comtesse de Noailles, my dame d’honneur, the superintendent of my household while I was dauphine and my de facto guardian. As the youngest daughter of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, I had come to Versailles at fourteen to wed the dauphin; and had been not merely educated, but physically transformed in order to merit such an august union. Yet, there had still been much to learn and little time in which to master it. The comtesse had been appointed my mentor, to school me in the rigid rituals of the French court. For this I had immediately nicknamed her Madame Etiquette, and in the past four years not a day had gone by that I had not received from her some rebuke over a transgression of protocol. Just behind my right shoulder the princesse de Lamballe stood amid my other ladies. Our wide skirts discreetly concealed another of my attendants, the marquise de Clermont-Tonnerre, who had sunk to her knees from exhaustion. I heard a giggle. The marquise was known to pull faces from time to time and kept all of us in stitches with her ability to turn her eyelids inside out and then flutter them flirtatiously.

“Who are you hiding?” quizzed Madame de Noailles. My ladies’ eyes darted from one to another, none daring to reply.

“La marquise de Clermont-Tonnerre est tellement fatiguée,” I replied succinctly.

“That is of no consequence. It is not comme il faut. Everyone must stand during the reception.”

I stepped aside. “Madame la marquise, would you kindly rise,” I commanded gently. With the aid of a woman at either elbow she stood, and the vast swell of her belly straining against her stays was as evident as the sheen on her brow. “I believe you know the comtesse de Noailles,” I said, making certain Madame Etiquette could see that the marquise was enceinte. “I am not yet a mother, mesdames, although I pray for that day. I can only hope that when it comes, common sense will take precedence over protocol. And as queen, I will take measures to ensure it.” I offered the marquise my lace-edged handkerchief to blot her forehead. “As there is nowhere to sit, you may resume your former position, madame, and my ladies will continue to screen you from disapproving eyes.”

I glanced down the hall, noticing the line of courtiers stopped in front of Louis a few feet away. There was much daubing of eyes, yet only his were genuinely moist. Then I returned my attention to the comtesse de Noailles. We were nose to nose now; and I was no longer an unruly child in her custody. One mother who scolded me at the slightest provocation was sufficient; I had no need of a surrogate. “You and your husband have served France long and faithfully,” I began coolly, “and you have devoted yourselves tirelessly without respite. The time has come, therefore, for you to take your congé. My husband and I will expect you to pack your things and retire to your estate of Mouchy before the week is out.”

Her pinched face turned as pale as a peeled almond. But there was nothing she could say in reply. One did not contradict the will of the Queen of France.

“The princesse de Lamballe will be my new dame d’honneur,” I added, noting the expression of surprise in my attendant’s eyes and the modest blush that suffused her cheeks. I had caught her completely unaware, but what better time to reward her loyalty?

The comtesse lowered her gaze and dropped into a deep reverence. “It has been an honor to have served Your Majesty.” The only fissure in her customary hauteur was betrayed by the tremolo in her voice. For an instant, I regretted my decision. Yet I had long dreamed of this moment. From now on, I would be the one to choose, at least within my own household, what was comme il faut. As the comtesse rose and made her way along the hall to offer her condolences to the king, I felt as though a storm cloud that had followed me about from palace to palace-Versailles, Compiègne, Fontainebleau-had finally lifted, leaving a vibrant blue sky.

#

At the hour of our ascension to the throne, after the requisite obsequies from the courtiers, we had fled the scene of Louis XV’s death nearly as fast as our coach could bear us, spending the first nine days of our reign at the Château de Choisy on the banks of the Seine while the innumerable rooms of Versailles were scrubbed free of contagion. Yet I was bursting to return, to begin making my mark. No one alive could recall when a queen of France had been much more than a dynastic cipher. Maria Theresa of Spain, the infanta who had wed the Sun King, was almost insignificant at court. She spent much of her time closeted in her rooms drinking chocolate and playing cards with her ladies and her dwarves, and had so little rapport with her subjects that when they were starving for bread she suggested that they eat cake instead-this much I had learned from my dear abbé Vermond, who had instructed me in the history of the queens of France when I was preparing to marry the dauphin. The mild-mannered abbé had accompanied me to Versailles as my reader, to offer me spiritual guidance, and he still remained one of my only confidants.

In any case, Maria Theresa of Spain had died nearly a hundred years ago. And her absence from public life had afforded Louis XIV plenty of opportunities to seek companionship in the arms of others. They, not his dull queen, became the arbiters of taste at court.

My immediate predecessor, Marie LeszczyÅ„ska, the pious consort of Louis XV who passed away two years before I arrived at Versailles, had been the daughter of a disgraced Polish king, forced to live in exile. She bore Louis many useless daughters, but only one dauphin to inherit the throne-the father of my husband-and he died while his papa still wore the crown. Like the queen before her, she endured a shadowy existence, maintaining her spotless propriety while my husband’s grand-père flaunted his latest maîtresse en titre. No one noticed what she wore or how she dressed her hair. Instead, it was Madame la marquise de Pompadour who had defined the fashion in all things for a generation. And then Madame du Barry, Louis XV’s last mistress, set the tone, but there was no queen to rival her-only me. And I had failed miserably, never sure of myself, always endeavoring to find my footing; desperate to fascinate a timid husband who could not bring himself to consummate our marriage. I had wasted precious time by allowing the comtesse du Barry to exert her influence, over the court and over Papa Roi, much to the consternation of my mother.

Yet I was determined to no longer be a disappointment. Not to Maman. Not to France. In the aftermath of Louis XV’s demise, the comtesse du Barry was now consigned to a convent. Her faithful followers at court, the “Barryistes,” would simply have to accustom themselves to the absence of her bawdy wit and gaudy gowns.

The condolences of the nobility at La Muette marked the end of the period of full mourning. When the last of the ancient courtiers had risen, the king and I made our way outside to the courtyard where the royal coach awaited us. I dared not voice my thoughts to Louis but I felt as though we had spent the past ten days in Purgatory and now, as the gilded carriage clattered over the gravel and out onto the open road toward Versailles where we would formally begin our reign, we were finally on our way to Heaven.

I had first entered the seat of France’s court through the back route in every way-as a young bride traveling in a special berline commissioned by Louis XV to transport me from my homeland. How eager he had been to show me Versailles, from the Grand Trianon with its pink marble porticoes, to the pebbled allées that led past the canals and around the fountains all the way to the grand staircase and the imposing château that his great-grand-père the Sun King had transformed from a modest hunting boîte into an edifice that would rival all other palaces in Europe. And oh, how disappointed I had been on that dreary afternoon: The fountains were dry, the canals cluttered with debris, and the hallways and chambers of the fairyland château reeked of stale urine.

How different now the aspect before me as we approached the palace from the front via the Ministers’ Courtyard. The imposing gateway designed by Mansart loomed before us, its gilded spikes glinting in the soft afternoon sunlight. I rolled open the window of the carriage and peered out. Then, turning back to my husband, giddy with anticipation I exclaimed, “Tell me the air smells sweeter, mon cher!”

“Sweeter than what?” Louis looked as if he had a bellyache, or a stitch in his side from a surfeit of brisk exertion. As neither could have been the case, “What pains you, Sire?” I asked. I rested my gloved hand in his. He made no reply but the pallor on his face was the same greenish hue as I recalled from our wedding day some four years earlier. He was terrified of what awaited him, fearful of the awful responsibility that now rested entirely upon his broad shoulders. And as much as I desired to be a helpmeet in the governance of the realm, I was no more than his consort. Queens of France were made for one thing only. And that responsibility, I was painfully aware, I had thus far failed to fulfill.

I pressed Louis’s hand in a gesture of reassurance. Just at that moment, the doors of the carriage were sprung open and the traveling steps unfolded by a team of efficient footmen. “Sois courageux,” I murmured. “And remember-there is no one to scold you anymore. The crown is yours.”

The Ministers’ Courtyard and the Cour Royale just inside the great gates were once again pulsing with people. The vendors had returned to their customary locations and were already doing a brisk business renting hats and swords to the men who wished to visit Versailles but were unaware of the etiquette required. The various marchandes of ribbons and fans and parfums had set up their stalls as well. I wondered briefly where they had been during the past two weeks. How had they put bread on their tables while the court was away?

My husband adjusted the glittering Order of the Holy Spirit which he wore pinned to a sash across his chest. But for the enormous diamond star, his attire was so unprepossessing-his black mourning suit of ottoman striped silk was devoid of gilt embroidery, and his silver shoe buckles were unadorned-that he could have easily been mistaken for a wealthy merchant. As we were handed out of the carriage into the bright afternoon, at the sight of my husband a great cheer went up. “Vive le roi Louis Seize!” How the French had hated their old king-and how they loved their new sovereign. Louis le Desiré they called my husband.

Louis reddened. I would have to remind him that kings did not blush, even if they were only nineteen. “Et mon peuple-my good people-vive la reine Marie Antoinette!” he exclaimed, leading me forth as if we were stepping onto a parquet dance floor instead of the vast gravel courtyard.

They did not shout quite as loudly for me. I suppose I had expected they would, and managed to mask my disappointment behind a gracious smile. When I departed Vienna in the spring of 1770 my mother had not so much exhorted, but instructed me to make the people of France love me. I dared not tell her that they weren’t fond of foreigners, and that even at court there were those who employed a spiteful little nickname for me-l’Autrichienne-a play on words, crossing my nationality with the word for a female dog. Didn’t Maman realize that France had been Austria’s enemy for nine hundred years before they signed a peace treaty with the Hapsburgs in 1756? Make the French love me? It was my fondest hope, but I had so many centuries of hatred to reverse.

The courtyards teemed with the excitement of a festival day. Citizens, noisy, curious, and jubilant, swarmed about us as we made our way toward the palace. A flower seller offered me a bouquet of pink roses, but I insisted on choosing only a single perfect stem and paying for it out of my own pocket. Sinking to her knees in gratitude, she told me I was “three times beautiful.” I thanked her for the unusual compliment and tried to press on through the crowd. After several minutes of jostling and much waving and smiling and doffing of hats, we finally reached the flat pavement of the Marble Courtyard and the entrance to the State Apartments.

For days I had imagined how it would feel to enter Versailles for the first time as Queen of France. I rushed up the grand marble staircase clutching my inky-hued mourning skirts, anxious to see my home, as I now thought of it-my palace. Would I view it through new eyes, now that I was no longer someone waiting-now that I had become?